Earlier this week, Karen Mills, the current Administrator of the Small Business Administration (SBA), announced her intention to leave office, opening up another second-term vacancy for President Obama to fill in the coming months. The SBA position is unlikely to attract as much media attention or pundit speculation as the EPA or Energy Interior posts, but it could have a big impact on whether the Obama Administration is able to take on the long to-do list of public health, safety, and environmental challenges that the nation currently faces. The next SBA Administrator can and should begin the critical process of reshaping the controversial SBA Office of Advocacy so that it focuses on helping truly small businesses, without undermining regulatory safeguards.

A recent CPR white paper I co-authored examined how the Office of Advocacy uses federal tax dollars to try to block health, safety, and environmental regulations, often at the behest of large companies. This small and largely unaccountable office, the paper argues, exerts significant influence over the federal rulemaking process, and its work all too often does not benefit truly small business. Rather, the Advocacy office typically echoes the viewpoints of large corporate interests who are already well represented in the rulemaking process, often with the result of watering down or bottling up safeguards needed to protect people and the environment against unreasonable risks.

The white paper concludes by offering several recommendations aimed at creating a more productive role for the Office of Advocacy to play in the federal regulatory system. First, it recommends reorienting the Advocacy office’s mission so that it works toward promoting small business competitiveness—that is, finding ways to help small businesses meet effective regulatory standards without undermining the capacity to compete with larger firms (what we call “win-win” regulatory solutions). Second, mindful that some of the "small" businesses the Advocacy office thinks are its constituents have as many as 1,500 employees, the white paper recommends restricting the Advocacy office’s focus to truly small firms—those with 20 or fewer employees—which lack the resources and expertise to participate meaningfully in individual rulemakings on their own.

Full textYesterday, the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) finalized the long overdue Pattern of Violations rule, a measure that will enhance the agency’s enforcement authority by making it easier for the agency to hold scofflaw mines strictly accountable for repeatedly and needlessly putting their workers at risk of chronic illness, severe injury, or even death. The deterrent effect of this enhanced enforcement authority will discourage delinquent mine operators from cutting corners on health and safety, a development that will produce significant benefits for America’s miners. MSHA estimates (see page 6) that the rule will prevent nearly 1,800 non-fatal injuries over the next 10 years, in addition to reducing instances of illnesses and fatalities.

The Pattern of Violations rule was one of the high priority regulatory actions that MSHA announced in response to 2010’s Upper Big Branch Mine disaster, in which 29 miners were killed in a massive mine explosion. Several investigations of the incident revealed that the explosion was precipitated by a deadly combination of hazardous conditions including improperly maintained mining equipment, inadequate ventilation, and insufficient rock dusting; the Upper Big Branch Mine had had been repeatedly cited for many of these kinds of hazards in the months prior to the disaster. Between 2005 and the time of the explosion, MSHA had cited the Upper Big Branch Mine for 1,342 violations. In 2009 alone, the agency cited the mine for 515 different safety violations, around 200 of which MSHA deemed to be “significant and substantial,” or violations that could reasonably be expected to lead to a serious injury or illness. The Upper Big Branch Mine’s operator—the now defunct Massey Energy Company—also had a long history of operating mines with similar health and safety violations.

Under the existing rules, delinquent mines that in practice had a long pattern of violations could avoid official “pattern of violations” status—which would enable MSHA to order the mine to withdraw workers from any part of the operation that it subsequently finds to have a significant and substantial violation—by appealing the citations. The Massey Energy Company had resorted to that tactic with Upper Big Branch, and MSHA had also made an error that stopped the company from moving a step closer to receiving a pattern of violation notification. Had a proper Pattern of Violations rule been in place, and had MSHA properly implemented it, the Upper Big Branch Mine disaster might have been prevented.

Full textInternal EPA emails obtained by CPR though a FOIA request reveals that representatives from one or more of the EPA’s peer agencies second-guessed a critical scientific finding undergirding the EPA’s then-pending draft final rule to tighten the ozone standard, claiming that ozone is not associated with mortality impacts. The EPA’s final proposal rightly disregarded the unsound comments and included information on how reducing ozone pollution saves lives. The rule, estimated to save thousands of lives, was later blocked by the White House. The email provides a rare glimpse at how peer agencies abuse the interagency commenting process by attacking other agencies’ rules—often on matters on which they have comparatively little expertise.

In the August 3, 2011, email, sent while the draft final rule was still undergoing review at the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), Karen Martin, an EPA scientist who was working on the rule, provided her colleagues her initial impressions on the interagency comments regarding the rule, which OIRA had just recently forwarded to the EPA. Martin noted that some commenters, un-named staff from one of the EPA’s peer agencies, questioned the EPA’s assumption that higher ozone levels contribute to premature deaths. Martin directly quoted a “set of commenters” who recommended that “EPA remove the assumption that ozone is associated with mortality impacts.” The interagency comments themselves are not available publicly and were not included in the batch of documents sent by EPA in response to CPR's FOIA request.

While technical-sounding, the assumption about the relationship between elevated ozone levels and premature deaths formed a critical part of the agency’s regulatory impact analysis for the rule. (The draft final analysis, which was the subject of the interagency complaints, is available here.) In the regulatory impact analysis, the agency explains that it included this assumption at the recommendation of the National Academy of Science (see page 3). The monetized benefits of preventing ozone-related mortality was to be the second largest source of the rule’s benefits (see page 34); thus, the failure to include these benefits would serve only to distort the rule’s cost-benefit analysis more. (As practiced, several inherent methodological flaws lead cost-benefit analysis to over-count costs while under-counting benefits, rendering it systematically biased against protective regulations.)

Full textThe Vice Presidential debate is tonight, and I suspect that, among other things, we’ll hear Paul Ryan give some general talk of “reducing red tape” or “reducing government burdens on job creators.” We probably won’t hear a pitch for blocking air pollution rules that would save thousands of lives—which, after all, doesn’t poll well. But that’s exactly what Ryan has voted for, over and over.

Representative Ryan’s record on regulations and the environment has received relatively little attention outside an initial burst in the environmental press, probably because he’s pitched himself on his budget, and has no real environmental initiatives specifically to his name. (Note that his extreme budget proposal, which would slash federal discretionary spending, would devastate the federal agencies charged with protecting the public—though of course we don’t get to hear the specifics, which would be quite unpopular).

What hasn’t gotten much attention, though, is the dozens of times that Ryan has voted to limit agencies’ ability to carry out their statutory mission of protecting people and the environment—most notably his repeated votes to undo critical provisions of the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments. If enacted, these bills would undermine the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) ability to protect people and the environment against the risks of toxic air pollution. That a candidate for Vice President has publicly supported gutting the Clean Air Act is remarkable. Yet in the era of a new normal for Congressional Republicans—where most of them voted for these bills—Ryan’s positions have generally escaped public scrutiny.

Full textToday, the EPA announced its new proposed National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) for fine particulate matter, commonly referred to as soot. Soot is one of the most common air pollutants that Americans encounter, and it is extremely harmful to our health and the environment, contributing to premature death, heart attacks, and chronic lung disease. Today’s proposal is a significant step forward that will bring tremendous benefits for the public if and when it is finalized.

The proposal comprises two parts—an annual standard and a daily standard. EPA is proposing to maintain the daily standard of 35 micrograms per cubic meter of air (hereafter “micrograms”), while lowering the annual standard from 15 micrograms to within the range of 12 to 13 micrograms. Significantly, this proposal is consistent with the recommendation of the EPA’s scientists, which was endorsed by the Clean Air Science Advisory Committee (CASAC), a committee of leading independent air pollution experts established by the Clean Air Act to advise the agency on the science underlying Clean Air Act rules.

The EPA is to be commended for issuing a soot NAAQS proposal that is supported by the law and science. Under the Clean Air Act, the agency must set the soot NAAQS at a level that is protective of human health with an adequate margin of safety. Congress intended this standard to protect the most vulnerable members of our society, including children, the elderly, and the chronically ill, and, as the US Supreme Court has recognized, this standard explicitly forbids the consideration of any regulatory costs. The Clean Air Act further directs the agency to review the underlying science for the standard at least once every five years; if the science shows that the existing standard is not protecting human health with an adequate margin of safety, the agency must set a stronger standard that meets this health-protective goal.

Full textLast December, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) finalized a new aviation safety rule designed to prevent excessive pilot fatigue, a problem that had contributed to at least one high-profile airline disaster—the Colgan Air Flight 3407 crash near Buffalo, New York, in February of 2009, which killed 50 and injured four—as well as to a disturbing series of mishaps and “near misses.”

It turns out that the rule took a mid-flight detour on its journey from proposal to final form, and that the way in which it was weakened along the way is a textbook example of how the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs manages, at the behest of industry, to override the plain meaning of statutes requiring regulation. The proposal, issued for public comment in September 2010, covered cargo-only pilots as well as passenger pilots. That made a certain sense, because while cargo-only pilots don't carry as many passengers, they're still flying big aircraft, the safe operation of which requires an attentive pilot. But when the final rule came out in December, cargo-only pilots were exempted. In their comments, some members of the cargo-only airline industry had suggested that the FAA amend the proposal to include this exemption, arguing that the costs of the rule outweighed the benefits of preventing all-cargo planes from crashing. According to the draft final rule, however, the FAA had rejected this suggestion.

If the public comments hadn’t persuaded the FAA that an exemption for all-cargo pilots was appropriate, then what could have changed the agency’s mind at the last minute? A close review of the record reveals that the rule was weakened at the behest of the OIRA. A red-lined version of the final rule showing all the changes that had been made to the draft while it was under OIRA review confirms that this exemption was added during OIRA's review process. What’s more, the red-lined version shows that OIRA directed the FAA to include new language in the rule’s preamble justifying this change solely on the basis of cost-benefit analysis, with clear disregard for applicable law and relevant science.

A little background is in order. In 2010, following the Colgan Air disaster, Congress passed the Airline Safety and Federal Aviation Administration Extension Act. In the disaster’s aftermath, investigators attributed the crash primarily to pilot error arising from excessive fatigue; regional pilots, such as those employed by Colgan Air, frequently log long, irregular hours with inadequate time in between shifts to rest properly. The new legislation directed the FAA to take several steps to prevent future fatigue-related plane disasters, including issuing a new regulation establishing maximum flight and duty times for pilots and other flight crew members as well as minimum rest periods between shifts. Significantly, Congress directed the FAA to base these new regulations on the “best available science information” related to fatigue and human sleep requirements.

Full textInside EPA is reporting that yet another critical EPA rulemaking is now being delayed indefinitely. This time it’s the agency’s rulemaking to codify a draft guidance clarifying whether Clean Water Act protections apply to wetlands and other marginal waters.

EPA had projected on its online rulemaking gateway that it expected to issue a proposed rule this month. In the recent Issue Alert that CPR President Rena Steinzor and I wrote, we were skeptical about this deadline, because the EPA has not yet even sent a draft proposal to the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) for centralized review—a process that often takes several months, and in some cases well over a year.

The Inside EPA article notes that the EPA’s rulemaking gateway was changed at some point since March 5th, so that it now provides no deadline for issuing a proposal. The article also says that Ellen Gilinsky, senior policy adviser for EPA’s Office of Water, said at an event on Monday that “We're continuing to work with the Corps on a rulemaking, but we have no schedule right now.”

The rulemaking has drawn fierce opposition by the agricultural and oil and gas development industries, among others, as well as by their allies in Congress, because it would effectively expand protections for these waterbodies, which provide such invaluable ecosystem services as controlling non-point source pollution, preventing flooding, and providing critical habitat to endangered and migratory species. The rule will eliminate the regulatory uncertainty that has cropped up following a muddled Supreme Court opinion, which has caused drops in enforcement and protection of our waters. Ironically, industry and congressional Republicans blame just such regulatory uncertainty for holding back the economy, as part of their crusade against critical safeguards.

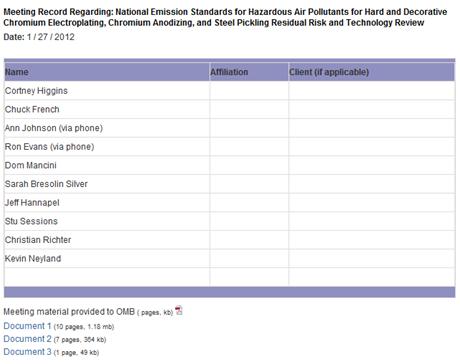

Full textIn its public meeting records, the White House’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) frequently misspells the names or affiliations of the attendees. Senator Jon Kyl was once listed as “Sen. Rul.” And John Ikerd, affiliated with the University of Missouri (MO) and the Sierra Club, was listed as “John Ikend, University of MD/Siemen Club.”

Sometimes the misspelled names or affiliations are easy to figure out; other times they aren’t (see page 77 of our OIRA white paper from November for more examples). The public is supposed to be able to tell who these people are – that’s the whole point, transparency.

The misspellings are troublesome, but a new OIRA meeting record I just noticed takes the cake for leaving the public uninformed:

Why list the affiliation of the attendees at all?!

The occasional typo is one thing, but when OIRA gets it wrong so regularly – or now simply leaves out the affiliations of individuals seeking to influence the outcome of public health and environmental safeguards – it’s a mission-defeating problem.

Full textSoon after assuming office in January 2009, President Obama promised that, in contrast to George W. Bush, science and law would be the two primary guiding stars for regulatory decision-making during his administration. From that perspective then, the finalized version of the EPA’s ozone standard should have been a no-brainer. After all, the standard was intended to replace the 2008 one issued in the dying days of the Bush Administration, which EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson has slammed as legally and scientifically indefensible. The Clean Air Act charges the EPA to set the ozone standard at a level that is protective of human health with an adequate margin of safety, and, consistent with this mandate and with the unanimous recommendation of the EPA’s blue ribbon clean air science advisors for how to achieve this mandate, the agency seem poised to set the new standard somewhere between 60 and 70 parts per billion (ppb).

Then politics—in the face of OIRA Administrator Cass Sunstein and White House Chief of Staff Bill Daley—intervened. The Obama Administration turned its back on both science and the law, and ordered Administrator Jackson to stop working on the new ozone standard. Under the circumstances, Obama wasn’t in the greatest position to justify this abrupt about-face.

Not surprisingly, the return letter from Sunstein formally rejecting the ozone rule betrayed more than just a mere soupçon of desperation. Drawing on Executive Order 13563, Sunstein relied in part on two novel considerations—regulatory uncertainty and the current economic situation—to justify the retreat. Then, without a hint of irony, Sunstein went on to claim that the decision was compelled in part by considerations of scientific integrity:

Full textWhat would you do if a report you funded was debunked by a scathing critique from the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service? What if you found that the researchers you funded had based 70 percent of their analysis of the costs of regulation on a regression based on opinion polling data? What if the researchers who had published that opinion polling insisted publicly that their data was never meant to be used for such purposes? What if a member of Congress had publicly lambasted you for keeping the underlying data used in the study from being examined by the public?

For the Small Business Administration’s Office of Advocacy, the answer appears to be: Stay the Course. In new research proposal requests I noticed recently posted on the SBA’s website, the SBA appears to have learned little.

The Office of Advocacy’s flawed report that got so much attention is cited regularly by anti-regulatory Members of Congress who like to repeat over and over the study’s thoroughly discredited contention that regulations cost the U.S. economy $1.75 trillion each year. The study itself was written by economists Nicole Crain and Mark Crain, under a contract from SBA’s Office of Advocacy (“Advocacy”).

Full text