This post was written by Member Scholar Amy Sinden and Policy Analyst Lena Pons.

This morning President Obama will make an announcement about upcoming fuel economy and greenhouse gas emission standards for passenger cars and light trucks for model years 2017-2025. The announcement will reference the Administration’s plan to propose a standard to reach 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025. These standards will set the pace at which automakers improve the fuel economy of cars for many years to come, and help to determine how quickly advanced technologies – plug-in hybrids, electric vehicles, and fuel cell vehicles – will be available in showrooms.

But the planned announcement is troubling because the number the President will roll out was the result of raw political wrangling, not the rational policymaking process that the Administration purports to pride itself on. The White House has been haggling with the automakers for the last month, and 54.5 is the magic number that has emerged from that negotiation.

This is not how the process is supposed to work. Under the laws passed by Congress, the agencies are supposed to go through a rational scientific process in order to set the standard at the “maximum feasible” level. Once the agencies – in this case the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and EPA – have gone through that process and come up with a tentative number, then they are supposed to go through the notice and comment rulemaking process. That means they publish their proposed rule along with a detailed explanation of their proposal and supporting information. Then everyone, including the automakers, is invited to comment on the proposal and attempt to persuade the agencies of how the initial proposal should be modified. The comments of all interested parties are public, and everyone is theoretically included in the process. This process is not new or unfamiliar. It is one of the fundamental tenets of Administrative Law.

Full textThis item, cross-posted from Triple Crisis, was written by CPR Member Scholar Frank Ackerman and fellow Stockholm Environment Institute-U.S. Center economist Elizabeth A. Stanton.

Your house might not burn down next year. So you could probably save money by cancelling your fire insurance.

That’s a “bargain” that few homeowners would accept.

But it’s the same deal that politicians have accepted for us, when it comes to insurance against climate change. They have rejected sensible investments in efficiency and clean energy, which would reduce carbon emissions, create green jobs, and jumpstart new technologies – because they are too expensive.

While your house might not burn down, your planet is starting to smolder. Extreme weather events are becoming more common, and more expensive: in the first half of 2011, Mississippi River floods cost us between $2 and $4 billion, while the ongoing Texas drought has cost us between $1.5 and $3 billion, according to the National Climatic Data Center. And there’s much worse to come: climate-related extremes are already forcing millions of people from their homes worldwide; ice sheets and glaciers are melting much faster than expected; the latest research shows we are rapidly heading for summer temperatures at which crop yields in America will start to plummet.

Full text Imagine you are building a beach house somewhere on the Gulf Coast and that I had some information about future high tides that would help you build a smarter structure, avoid flood damage, and save money in the long-run. Would you want that information?

Imagine you are building a beach house somewhere on the Gulf Coast and that I had some information about future high tides that would help you build a smarter structure, avoid flood damage, and save money in the long-run. Would you want that information?

Not if you follow the reasoning of Representatives Steve Scalise of Louisiana or John Carter of Texas. Both are concerned about the Obama administration’s recent efforts to make federal programs stronger and more resilient in the face of climate change. Scalise sponsored an amendment (H.AMDT. 467 to H.R. 2112) that prevents the Department of Agriculture (USDA) from pursuing its plan to assess climate vulnerabilities in its programs. Carter did the same (H.AMDT. 378 to H.R. 2017) for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). And this month the Republican-led House of Representatives, with little fanfare, passed both initiatives (Scalise roll call, Carter roll call). I doubt either proposal will move past the Senate, but these efforts show how far some in the Republican Party have drifted from the geographic realities of their own states. And they underline the point that in the next election cycle Republicans seem likely to oppose any initiative whatsoever intended to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions or help with adapting to a changed world.

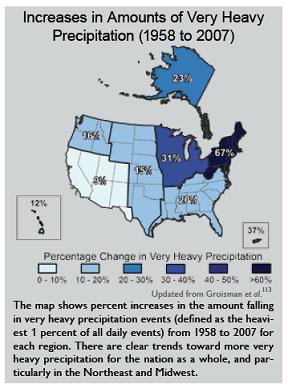

Forgive me for saying so, but our climate is changing. In the last 50 years, the ambient temperature in the United States has risen 2 degrees Fahrenheit. Overall precipitation in that time has increased by 5 percent. The amount of rain falling in the heaviest downpours in the United States has increased an average of 20 percent in the past century. In the last 40 to 50 years, many types of extreme weather events like heat waves and droughts have become more frequent and intense. Coastal storms in the Pacific and Atlantic have also intensified. And in the last half-century, sea level has risen up to 8 inches or more along some areas of the coastal United States. These trends are expected to continue or accelerate into the future. This information and more is available in the 2009 report, "Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States," issued by the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP), a consortium of thirteen federal agencies and departments. This peer-reviewed survey synthesizes a mountain of direct observations and other data accumulated over the last one hundred years.

Full textCPR Member Scholar Doug Kysar has a post over at Nature with more analysis on the Supreme Court's ruling this week in the American Electric Power v. Connecticut case. Writes Kysar:

The court went out of its way to emphasize that federal common-law actions would be barred, even if the EPA decides not to regulate greenhouse-gas emissions. In other words, the fact that the agency has authority under the Clean Air Act — even if it chooses not to exercise it — was enough, in the court's view, to cut the judiciary out of the equation, stating, "We see no room for a parallel track."

The problem with this is that the US system of limited and divided government is a web of interconnected nodes, not a row of parallel tracks. The courts should understand that part of judges' role is to prod and plea with other government branches, which may be better placed to address an area of societal need, but are less disposed to try.

Full text

Cross-posted from Legal Planet.

The Supreme Court decided the AEP case. The jurisdictional issues (standing and the political question doctrine) got punted. The Court said that the lower court rulings were affirmed by an equally divided court. So far as I know, this is the first time that the Court has ever done that and then proceeded to a ruling on the merits. (It would seem more appropriate to dismiss cert. as improvidently granted rather than issue an opinion on the merits.) This is actually good news: it means that there were four Justices to reject the political question doctrine and find standing. Since Justice Sotomayor did not participate but wrote the lower court opinion, we know that five Justices would vote accordingly in another case. Hence, it seems clear that lower courts should not apply the political question doctrine in these circumstances and that they should extend standing to climate change cases beyond the strict confines of Massachusetts v. EPA.

On the merits, the Court held that the federal common law of nuisance regarding climate change is preempted by the Clean Air Act’s grant of jurisdiction to EPA to regulate greenhouse gases. This part of the opinion strongly reaffirms the holding in Massachusetts v. EPA. According to today’s opinions,

Massachusetts made plain that emissions of carbon dioxide qualify as air pollution subject to regulation under the Act. 549 U. S., at 528–529. And we think it equally plain that the Act “speaks directly” to emissions of carbon dioxide from the defendants’ plants.

In a concurrence, Justices Alito and Thomas said they were taking this position only for the purposes of argument since no party had contested it. Notably, Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Scalia did not join them, so there seem to be six votes (plus Sotomayor) to uphold EPA jurisdiction at this point.

Finally, the plaintiffs are left with a possible claim under state law. The Court did not reach the question of whether that claim is viable since the issues were not briefed or argued.

Overall, this is about as good an outcome as could have been hoped for after oral argument. It also makes it more complex for Congress to repeal EPA jurisdiction since doing so would restore the federal common law claims.

Full textCopenhagen—Denmark’s famed "Little Harbor Lady," or in English, "Little Mermaid," has had her share of antics and perils. She’s been photographed by millions in Copenhagen’s harbor, carted off and shown at the 2010 World Fair in Shanghai, beheaded (several times), dynamited, splashed with pink paint, and enveloped in a Burqua. An environmental nerd for all occasions, I look at her longing face and wonder, How long before the rising sea swallows her up? Bolted to that rock in the sea, a shaft a concrete now inserted into her neck, what will she do? Or, for that, matter, the thousands of others who call coastal Copenhagen home. Is anyone thinking about this?

Many experts expect the world’s seas to rise somewhere between 1 to 1.5 meters this century, depending on location (and, of course, it could be more). Add to this a potential for stronger storms and much higher storm surges and you see why cities like Copenhagen, London, New York, and Miami are all in the crosshairs.

Danish experts have begun using computer-enhanced mapping techniques to predict what a high-tide of 2.26 meters—what they believe a "20-year event" might look like in 2110—would do to the city. The result leaves an inner city map covered in blue, including the Danish Stock Exchange, the Royal Library, and the city’s stunning Opera House. For this reason, the country is developing a proposal for a dike along Copenhagen’s North Harbor and an area called Kalveboderne to protect some of the city’s most treasured assets. For areas lying outside the protected region, which includes the Opera House, engineers are considering elevating roads and introducing architectural adjustments.

Back in New Orleans, where I live, we are also strengthening our fortress walls. At the opening of hurricane season this month, city residents took comfort (perhaps) in the strongest flood-control system ever constructed for the region. My favorite part is the Lake Borgne Barrier, a 1.8-mile-long castle-toothed wall, anchored by 66-inch-wide, 144-foot-deep concrete columns. The structure, which cost $1.1 billion and was built in just two years, is designed to block the kind of crashing hurricane surge brought by Hurricane Katrina, which in 2005 swept through the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway and Industrial Canal into the heart of New Orleans.

As I continually remind my students, resistance, while expensive and complicated, is not always futile....

Full textThe scope of climate change impacts is expected to be extraordinary, touching every ecosystem on the planet and affecting human interactions with the natural and built environment. From increased surface and water temperatures to sea level rise and more frequent extreme weather events, climate change promises vast and profound alterations to our world. Indeed, scientists predict continued climate change impacts regardless of any present or future mitigation efforts due to the long-lived nature of greenhouse gases emitted over the last century.

The need to adapt to this new future is crucial. Adaptation may take a variety of forms, from implementing certain natural resources management strategies to applying principles of water law to mimic the natural water cycle. The goal of adaptation efforts is to lessen the magnitude of these impacts on humans and the natural environment through proactive and planned actions. The longer we wait to adopt a framework and laws for adapting to climate change, the more costly and painful the process will become.

Today CPR releases a new report, Climate Change and the Puget Sound: Building the Legal Framework for Adaptation, which identifies both foundational principles and specific strategies for climate change adaptation across the Puget Sound Basin. The projected impacts themselves of climate change in the region were well studied in a landmark 2009 report by the state-commissioned Climate Impacts Group. Our report analyzes adaptation options within the existing legal and regulatory framework in Washington. Recognizing the economic and political realities may not lead to new legislation, the recommendations in the report focus on how existing laws can be applied and made more robust to include climate change adaptation.

Full textBonn--At a climate conference in Germany, with lager in hand, I was prepared to ponder nearly any environmental insult or failure. But rat pee? Really?

The urine of rats, as it turns out, is known to transmit the leptospirosis bacteria which can lead to high fever, bad headaches, vomiting, and diarrhea. During summer rainstorms in São Paulo, Brazil, floodwaters send torrents of sewage, garbage, and animal waste through miles of hillside slums and shanties. Outbreaks of leptospirosis often follow the floods. And in a metropolitan region of 20 million people, that’s a public health emergency.

I learned this and more at the 2nd World Congress on Cities and Adaptation to Climate Change, organized by ICLEI-Local Governments for Sustainability and the World Mayors Council on Climate Change, with support from the U.N. Human Settlements Programme. The event brought together 600 delegates, including mayors and UN officials, to address what may be this century’s defining challenge: keeping up with the climate.

While some of our national politicians continue to ignore basic climate science, and while I continue to rail against my local climate-denying weatherman who just last month spoke to my kids’ elementary school, the rest of the world is getting on with life. Specifically, scores of municipal governments from all over the world—rich and poor, iconic and ordinary—are beginning to make plans for adjusting to a planet that is going to be warmer, wetter, and just plain weirder.

In consultation with the World Bank, the City of Jakarta, Indonesia, has launched an assessment of geographical hazards, socioeconomic vulnerabilities, and institutional weaknesses now posed by rising seas, hotter temperatures, and swifter storms. This coastal megacity, 40 percent of which lies below sea level and is sinking because of groundwater depletion, is developing comprehensive disaster management programs, plans for coastal fortification, and new storm water systems. Half-a-world away, the city of Toronto has employed sophisticated computer modeling and a set of 1,700 plausible future scenarios to prepare for the impacts of stronger snowstorms and wilder floods. They have excel spreadsheets (and accompanying PowerPoint slides) on just about everything—traffic-light outages, sewer overflows, falling bridges, you name it. And down south in São Paulo, city officials are calling for vital “slum upgrades,” safer zoning, and, yes, improvements to sanitation and public-health networks to prevent and treat leptospirosis.

Full textCross-posted from Legal Planet.

I’ve just spent some time reading the initial briefs in the D.C. Circuit on the endangerment issue. They strike me as much more political documents than legal ones.

A brief recap for those who haven’t been following the legal side of the climate issue. After the Bush Administration decided not to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act, the Supreme Court held that greenhouse gases would be covered if they met the statutory requirement of endangering human health or welfare. After much stalling by the Bush administration, EPA followed the scientific consensus by finding that (1) yes, climate change is real and caused by human emissions of greenhouse gases, and (2) that climate change would indeed harm humanity (including Americans). That determination is now being challenged by states such as Texas and Virginia and various other parties like the Chamber of Commerce.

Why do I say that the documents seem more legal than political to me? Two reasons: they rely on debaters’ points that don’t survive examination of the record, and they are crafted to appeal primarily to ideological fellow-travelers rather than the open-minded.

Full textOn Wednesday, Our Children's Trust, an Oregon-based nonprofit, made headlines when it began filing lawsuits on behalf of children against all 50 states and several federal agencies alleging that these governmental entities have violated the common law public trust doctrine by failing to limit greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change. The claims seek judicial declaration that states have a fiduciary duty to future generations with regard to an “atmospheric trust” and that states and the federal government must take immediate action to protect and preserve that trust. Although these claims certainly are novel and may have limited or no success in many states because of lack of precedent, they rely on what has proved to be a flexible and powerful common law doctrine in some states that has pushed the legal envelope in the name of environmental protection in the past. As a result, these cases bear watching both as to their legal effect as well as the possibility that they will galvanize a broader base of grassroots support for action on climate change.

The public trust doctrine is a concept dating back to Roman Law which holds that there are certain natural resources that are forever subject to government ownership and must be held in trust for the use and benefit of the public. In the United States, plaintiffs have used the public trust doctrine successfully to prevent states and other governmental entities from conveying public trust resources such as submerged lands or municipal harbors into private ownership, to create public beach access, and to otherwise ensure public access to water-based resources. Until the 1970s, however, the doctrine had little to do with environmental protection and instead was used almost exclusively to prevent the privatization of water-based resources or to preserve public access to fishing, boating, or commerce.

Full text